Ambrose & Henry

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

Ambrose & Henry

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

HOW TWO ICONOCLASTS INFLUENCED LITERARY AMERICA FOREVER

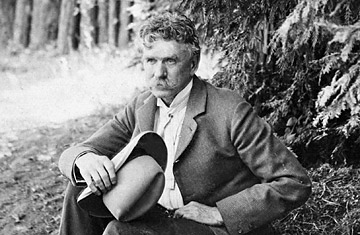

________________ A distance of thirty-eight years separated the two literary infidels. When they first met in the winter of 1911, Ambrose Bierce was sixty-nine and renowned. H.L. Mencken was thirty-one and on the cusp of achieving lasting prominence. Bierce was only two years from his infamous disappearance into Pancho Villa’s Mexican desert—while Mencken would write voluminously until 1948 when cut silent by a cataclysmic stroke. The occasion of their encounter was the funeral of the controversial literary critic Percival Pollard, who had died of a brain tumor at the age of forty-two in Baltimore on December 17. Except for their ages, the two writers had much in common. Both were journalists, both were enthralled by the English language, both were published authors, both had or would pen memoirs, both were partial to alcohol, both were religious skeptics, and both, in their time, were America’s greatest cynics. Physically, they were opposites. Bierce was tall, more than six feet, with blue eyes, blond hair and mustache turned to white, and strikingly handsome. Mencken was moon-faced, chubby ( “without muscles” as playwright and novelist Ben Hecht put it), hair parted in the middle, cigar usually clinched between his teeth. Certainly, Mencken knew of Bierce long before Bierce became aware of Mencken. In addition to his columns in the Hearst newspapers and Cosmopolitan Magazine, Bierce had published ten books, including his masterpiece, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1893), titled in Britain In the Midst of Life, the collection that included the classic story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” Mencken, in My Life as Author and Editor (published posthumously in 1993), writes, “...though I had a relish for Bierce’s epigrams, I thought his short stories rather artificial, and his critical writing—especially his insistence on what he chose to regard as ‘pure’ English—as decidedly second-rate.” Clearly, Mencken, perhaps intimidated and unconsciously influenced by the older writer, failed to give Bierce his proper due. It is likely that Bierce learned of Mencken through Percival Pollard, with whom Henry had corresponded, and possibly through Pollard’s influential critical work, Their Day in Court, published in 1909 by Walter Neale, who, incidentally, was Bierce’s publisher at the time. Pollard, in his book and with overly abundant commas, gushes over Bierce non-stop for thirty-one consecutive pages: “Ambrose Bierce, the only one of our men of letters sure to be heard of, side by side with Poe and Hawthorne, when our living ears are stopped with clay, committed, for most of his life, the fatal mistake of being, as well as a literary genius, a great journalist.” Pollard also mentions the youthful Mencken, but only in passing and only in connection with Mencken’s vision of Nietzsche as standing “aloof from his fellows.” By this time, the precocious Mencken had published six slim volumes, including The Gist of Nietzsche (1910), as well as his uncredited What You Ought to Know About Your Baby (1910), ghostwritten for Leonard K. Hirshberg, M.D. Ironies of ironies, six years earlier, Mencken had written hack advertising copy for Baltimore’s Loudon Park Cemetery. This was where Pollard’s body was to be cremated, and where Mencken himself would be buried alongside members of his family. Bierce’s grave remains unknown.  Pollard The unfortunate Pollard had written to Mencken to complain about splitting headaches. Henry, a hypochondriac and normally rational until it came to health, urged Pollard to travel to Baltimore for treatment. Mencken knew just the place, a small local hospital that specialized in homeopathy, the notion that gradual ingestion of diluted minerals and other substances would somehow enable the body to heal itself. Unlike Mencken, Bierce, who knew quackery when he saw it, wasn’t fooled. He sardonically called homeopathy (which he spells homoeopathy in his Devil’s Dictionary), “A theory and practice of medicine, which aims to cure the disease of fools. As it does not cure them, and sometimes kills the fools, it is ridiculed by the thoughtless, but commended by the wise.” In any event, Pollard’s wife brought the desperately ill critic to Baltimore from their home in New Milford, Connecticut. Bierce, a product of a struggling farm family of English ancestry, was born on June 24, 1842, in southern Ohio and reared hardscrabble in rural Indiana, although his father, a staunch opponent of slavery, boasted a decent library. Bierce once wrote, presumably of his childhood home, about “the scum-covered duck pond, the pigsty close by it, the ditch where the sour-smelling house drainage fell...” Four decades after Bierce’s earthly debut, Mencken arrived on September 12, 1880, in Baltimore, a metropolis of 400,000, to a well-to-do cigar manufacturer who produced such brands as La Cubana, Havana Rose, El Cabinet, Daisy, and La Mencken Paneta (although in adulthood Mencken smoked “Uncle Willies," rolled by the Schafer-Pfaf Company). Neither Bierce nor Mencken had earned more than high school educations. Mencken graduated from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, while Bierce spent one year at the now defunct Kentucky Military Institute in Lyndon, failing to graduate. Both men were essentially autodidacts, each read vociferously, and both developed determined and vocal opinions about what they read. Bierce, at sixteen, became a printer’s devil for the anti-slavery Northern Indianan in Warsaw. At nineteen, Mencken landed an unpaid job as a reporter for the Baltimore Morning Herald. Prospects were bleak for young Bierce, youngest of ten siblings (all of whose first names quixotically began with the letter A), until the outbreak of the Civil War. Enlisting as a private in the Ninth Regiment, Indiana Volunteers was the best decision he could have made. Although severely wounded in the battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, he recovered, earned the rank of brevet major, and entertained the notion of making the military his career. Bierce came of age during that terrible war, and its carnage influenced him and his writing morbidly, incalculably, and forever. On the other hand, in Baltimore, young Henry never experienced the military, certainly not warfare, although reporting on the great fire of 1904, which ravaged the heart of the city, proved to be a milestone in his life. As a journalist for the Herald, Mencken went into the conflagration as “a boy driven by the hot gas of youth,” he later said, only to emerge as “settled” and “almost middle-aged.”  Lt. Bierce (portrait by Tom Redman)  Mencken in the ‘hot air of youth.’ For a man who never experienced battle, Mencken was astonishingly flippant regarding war. In 1926, he wrote: “The pacifists who now rant in the open forums and suffragette magazines all seem to ground their case on the thesis that the people of the United States naturally abhor war and shrink from its horrors as an I.W.W. shrinks from soap. The notion, it seems to me, has a flavor of applesauce. It would be far more accurate, though plainly not the whole truth, to say that they delight in war and enjoy its gaudy uproar as a country boy enjoys circus day. ... As poor men go in this world, soldiers are well fed and well clothed and have very little work to do.” As much as Bierce wrote about war, he did not generalize. He allowed his personal experience on the field of battle speak for itself, such as what he saw at Shiloh: “Along a line...lay the bodies, half buried in ashes; some in the unlovely looseness of attitude denoting sudden death by the bullet, but by far the greater number in postures of agony that told of the tormenting flame. Their clothing was half burnt away—their hair and beard entirely; the rain had come too late to save their nails. Some were swollen to double girth; other shriveled to manikins. According to the degree of exposure, their faces were bloated and black or yellow and shrunken. The contraction of muscle which had given them claws for hands had cursed each countenance with a hideous grin. Faugh! I cannot catalogue the charms of these gallant gentlemen who had got what they enlisted for.” Unlike Mencken, Bierce was peripatetic. After the war, he served as a Treasury agent in Alabama, was a member of a military expedition through dangerous Indian territory, and worked as a watchman at the San Francisco Mint. He wrote and read and studied the night-hours away. Eventually, he wrote and edited for such California weeklies as The News-Letter and The Wasp. Later, he found himself as an expatriate writer in England (where he published his first three books under the pseudonym Dod Grile), as a failed gold mine operator in the Black Hills of Dakota, and—unexpectedly—a star-columnist with his own byline for William Randolph Hearst’s new San Francisco Examiner. Not only did Bierce become famous, he became arbiter, no matter how off the mark, of all that was then literary in California, earning himself the sobriquet “Wickedest Man in San Francisco.” Hearst, a man Bierce came to despise, dispatched him to Washington, D.C., in 1896 to serve as a fiery muckraker against the railroad barons. Bierce was successful, and three years later permanently relocated to the East on Hearst’s payroll. All the while, he published masterful short stories about war and the supernatural, attracting a bevy of youthful acolytes—among them George Sterling, George Scheffauer, and Edwin Markham—who believed he could do no wrong. He eventually outlived his long-estranged wife, Mollie, but two of his three children died prematurely and needlessly—tragedies that also shaped him. Mencken was permanently anchored to Baltimore, its heavily Germanic community familiar and reassuring, the blacks and the destitute hidden in the city’s back alleys—not far from where young Henry stabled his pony, Frank. Save for five happy years when he was married to sickly Sara Haardt, who died in 1935, Mencken lived at 1524 Hollins Street until the end. For most of his buoyant career he was affiliated with the once-prominent Sunpapers in both editorial and managerial positions. By 1911, the year of Pollard’s death, Mencken found himself in Who’s Who in America. His daily column in the Evening Sun, “The Free Lance”—in which he aimed his fire at prohibitionists, moralists, anti-vice crusaders, and reformers of all sorts—ran for four years. Even when he was co-editor (with George Jean Nathan) of, first, The Smart Set, later The American Mercury, Mencken chose never to abandon his beloved hometown, the nourishing Sunpapers, and his celebrated Chesapeake Bay crab dishes.  Mencken House, 1524 Hollins St., Baltimore Bierce, however, had no anchor to his past, and in most respects, his life was far more turbulent than Mencken’s—yet both men developed similar notions far askew from the prevailing attitudes of their times. By today’s perspective, they might be considered libertarian, vague as the term may be. Neither suffered fools and neither was reluctant to unleash invective against what he saw as the ignorant, the superstitious, and the criminal—yet each word they wrote was carefully turned with wit and a literary bearing. Politicians and preachers were the easiest and most delectable of targets. Rattling convention was what they did best and was how they thrived as writers. Strangely, in many ways, both were Victorian in their outlooks. Ambrose once said he’d never undressed nude before a woman, not even his wife, although he was not above making a pass at the young California novelist Gertrude Atherton, who rebuffed him. Mencken once joked that life would be perfect with a good sauce, a cocktail, and a girl who kissed with her mouth open, notwithstanding Henry’s usual cigar. For years, Percival Pollard, the literary critic of the New York weekly Town Topics, lashed out at what he saw as literary naturalism and mediocrity in the arts. His publisher, Walter Neale, said that “...Pollard was born sneering. ...He was to find much to sneer at. All his life he sneered; sneering, he died.” For example, Pollard wrote in Their Day in Court, “Why surely, anybody can write! Yes, and as we regard results, it often seems that—criticism being a dead letter—some of the people writing books must be people who, in any real cultured society, simply would never be allowed to open their mouths, much less put pen to paper. If I offered specimens of the rubbish shot almost weekly in book form, parading as English prose, or as human dialogue, there would be no room for anything else.” His final book, Vagabond Journeys, was issued the same day his body was cremated. While Bierce and Pollard did not meet face-to-face until after Bierce moved to Washington in 1899, they had been in contact by mail as early as July 1893. On October 18 of that year, Bierce, then in California, wrote to Pollard about the financial collapse of the F.J. Schulte Company of Chicago, which had published Bierce’s novelization of Richard Voss’s German folk tale The Monk and the Hangman’s Daughter. In the letter, Bierce cites his dispute with his “rascally" collaborator, Adolphe de Castro, “whom I recently had to thrash for lying and cheating.” In February 1904, shortly after the great Baltimore fire, Bierce and Pollard went to the city from Washington to survey the destruction. In the summer of 1905, Bierce vacationed for a month with Pollard at Sag Harbor, Long Island. They toured the Civil War battlefields in Tennessee in October 1907, then went on to Galveston and New Orleans, finally sailing to New York via Key West. By the time Mencken actually met Pollard in October 1910, the two had corresponded regularly over the previous four years. Mencken described Pollard as a “thorough-going Germanophile,” and praised the critic’s assertive masculinity as standing “forth like a truth seeker in the Baptist college of cardinals.” During his final illness, Pollard failed to respond to the homeopathic treatment recommended by Mencken, and a brain surgeon, Dr. Harvey Cushing, was called in. Cushing diagnosed a brain abscess and recommended emergency surgery, which was performed at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Pollard’s brain was laid open, and he died six days later without regaining consciousness. Pollard’s wife left the funeral arrangements to Mencken, who engaged an eccentric Episcopal priest, who was also an amateur cellist, to conduct the services. The rites were attended by just six mourners, including Bierce and Neale, who quoted Ambrose as saying, “Pollard in his time has roasted many, and now he is being roasted to a turn.” Bierce later wrote to his disciple, the poet George Sterling, “Yes, I’m a bit broken up by the death of Pollard, whose body I assisted to burn. He lost his mind, was paralyzed, had his head cut open by the surgeons, and his sufferings were unspeakable. Had he lived he would have been an idiot; so it is all right—” And to Silas Orin Howes, who in 1909 had published Bierce’s essay collection The Shadow on the Dial, Bierce wrote, “You would hardly care to have in memory the image of Pollard that I must carry for life. You’d have not recognized that handiwork of death. Poor Percy! He must have suffered horribly to become like that. Well, we put him into the furnace, as he would have wished, and there is no more Percy.” The funeral was Bierce’s first meeting with Mencken, who writes about it in Prejudices: Sixth Series (1927). Ambrose and Henry rode together to the crematory at Loudon Park Cemetery, and Mencken relates that Bierce’s conversation was superb, “...a long series of gruesome but highly amusing witticisms. He had tales to tell of crematories that had caught fire and singed the mourners, of dead bibuli whose mortal remains had exploded, of widows guarding fires all night to make sure that their dead husbands did not escape.” Mencken says Bierce suggested that Pollard’s ashes be presented to the New York Lodge of Elks or that they be mailed anonymously to Ella Wheeler Wilcox (a popular poet of the day known for the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you...” ). Bierce claimed to keep the ashes of his late son on his writing desk. When Mencken suggested that the ceremonial urn must be a formidable ornament, “’Urn hell!’ he answered. ’I keep them in a cigar box.’”  Loudon Park Cemetery, Baltimore Bierce’s ghoulish sense of humor at Pollard’s funeral was followed days later by a bizarre episode at the crematory, which was charging Mencken fifty-cents a day to store Pollard’s remains. When he went there to examine the ashes, Mencken found that the job was far from finished. There were still parts of Pollard’s bone matter as well as the skull bearing the marks of the surgeon’s drill. The attendant began to grind up the remains in a large mill. But the sound of crackling bones was too much for Mencken, who fled the cemetery. Later, Mencken was faced with the task of packaging Pollard’s remains and sending them to his final resting place in Washington, Iowa, where Pollard had spent his youth, but even that hit a snag. The postal clerk claimed the parcel containing Pollard’s ashes constituted a corpse and could not be mailed without a permit. Henry finally paid an undertaker fifteen dollars to remove the grisly task from his hands. Ambrose could not resist getting in a final shot, telling Mencken that the Christians in Iowa would dig up Pollard’s remains and throw them over the state line. Following the funeral, Mencken and Bierce saw each other on several occasions, sometimes at the Army and Navy Club on Farragut Square in Washington, where Bierce was an habitue of the club’s Daiquiri Bar. They also corresponded by mail. At first, Bierce addressed the younger writer as “Mr. Mencken," later as “My Dear Mencken.” On May 1, 1913, Bierce expressed surprise that Pollard’s widow had remarried “without my consent and doesn’t tell me about it. Alas, alas, for the fidelity of woman.” Mencken proposed that Bierce join him on the staff of a projected magazine, but Bierce declined, saying, “...I fear I am a bit too old and lazy for any regular connection with it—anything that would require consecutive work. I probably shall never again write anything but stories, and then only when the spirit moves me, or to fill a definite order. I do enjoy my idleness.” On April 25, 1913, Bierce revealed to Mencken his plans to cross the border. “...I shall go West later in the season—or rather Southwest—and may go to Mexico (where, thank God, there is something doing) and to South America. To that region if, in Mexico, I do not incur the mischance of standing against a wall to be shot.” His last letter to Mencken was dated May 25, 1913, joshing the younger man as being too courtly in his treatment of Socialism. “I should myself not think of opposing a Socialist otherwise than by a cuff upon the mouth of him... Observe that the fellow in jail for sending indecent matter through the mails is invariably a Socialist... All the same, Socialism is going to get our goat.” Walter Neale’s 1929 reminiscence of Bierce is dedicated to William Randolph Hearst, an irony since Bierce had a love-hate relationship with Hearst almost from the day the newspaper magnate hired him in 1887. Bierce vowed to write a book that would expose the publisher as a man of dangerous ambition, but not as long as Hearst’s mother was alive. Neale, however, praises Hearst for flinging open his newspaper doors to Bierce when no other American publisher would recognize him. Bierce’s sour relationship with Hearst spanned twenty-one years, ending in 1908. In 1936, Mencken was approached by the editor of the Hearst-owned Baltimore News with an offer. Hearst expected his seriously ill star-columnist Arthur Brisbane to soon die and wanted Mencken to take over the column. Hearst proposed a five-year contract at $1,000 a week, and promised that Mencken would be given a free hand to speak his mind. Mencken declined the offer, and ultimately Hearst wound up writing the column himself. Later, Mencken, as a representative of the Sunpapers, visited Hearst in New York with an offer to buy the News. This time, it was Hearst who declined, but he invited Mencken to visit him at his estate at San Simeon, California. Unlike Bierce, Mencken said the two departed on the best of terms. Both Bierce and Mencken shared a mutual love of the English language, although they differed sharply in its application. In a tiny but lively book called Write it Right (1909), Bierce railed against colloquialisms, saying that “few words have more than one literal and serviceable meaning, however many metaphorical, derivative, related, or even unrelated meanings lexicographers may think it worth while to gather from all sorts and conditions of men, with which to bloat their absurd and misleading dictionaries.” According to Bierce, “Slang is the speech of him who robs the literary garbage cans on the way to the dump.” Pollard was thoroughly on Bierce’s side, maintaining that “...no man in our time did more for English than Ambrose Bierce.” Mencken saw things differently. Ten years after Bierce’s little tome, Mencken published The American Language, the first of four editions. In it, he celebrates the ever changing pattern of the language, its pronunciation, spelling, and usage. On this, he and Bierce would never see eye-to-eye, but in taking such a rigid stand against the natural ebb and flow of language, Bierce was left far behind in history’s linguistic dust.

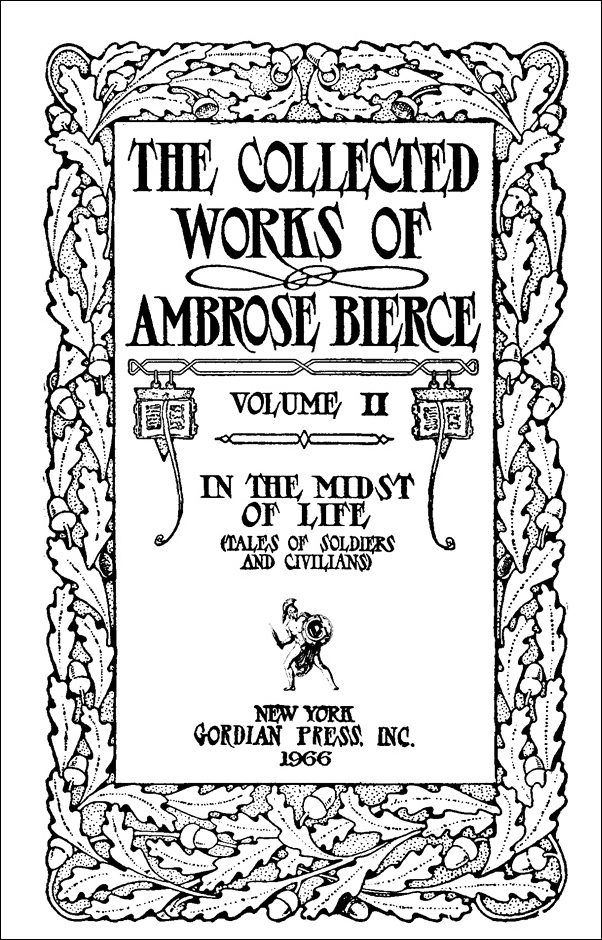

The two were close to agreement on issues of faith and religion. In a letter to a long-time friend, Mencken writes that all religions “...pretend to explain the unknowable... Anyone who pretends to say what God wants or doesn’t want, and that is what the whole show is about, is simply an ass.” For Bierce faith was, “Belief without evidence in what is told by one who speaks without knowledge of things without parallel.” With regard to music, Mencken was an accomplished pianist, favoring the German composers. “There are, indeed, only two kinds of music: German music and bad music.” Bierce was tone deaf. He described a violin as, “An instrument to tickle human ears by friction of a horse’s tail on the entrails of a cat.” His musical tastes were uncomplicated, and his favorite melody was Dvorak’s “Humoresque.” Mencken was a particular admirer of Mark Twain, and described Huckleberry Finn as one of the great masterpieces of the world. He claimed to have read it once a year. Bierce was less sanguine, having met Twain as a young man in San Francisco. But he told Neale, “Mark Twain is a far greater humorist, a far greater wit, than real men of letters seem to realize... He is as likely to live beyond our age as any of us.” As for alcoholic beverages, both men enjoyed tippling, and Mencken was a vehement opponent of Prohibition. “A poison?” Mencken asked rhetorically in 1911. “Certainly. But so are all other things that lift man out of himself, and make him soar and expand, and give him temporary forgetfulness of his wife’s lack of beauty, his bank account’s anemia and his own ungraceful figure, growing baldness and bad indigestion.” Bierce, who defined the word “abstainer” as “A weak person who yields to the temptation of denying himself a pleasure," was fortunate enough to have disappeared into Mexico by the time the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect in 1920.  Mencken celebrates Prohibition’s Death On June 1, 1908, Bierce and Walter Neale met for luncheon at the politically and literarily elite Harvey’s Restaurant, 11th and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, where the publisher proposed that he print everything Bierce had written that the author cared to preserve. A contract was signed and witnessed that very night at Bierce’s apartment at the Olympia. It stipulated that Bierce would have a free hand in the selection of writings for his Collected Works and that he supply material at the rate of at least two volumes a year. Neale would retain publication rights for twenty-five years, while Bierce would receive a royalty of twenty percent on all copies sold, not to exceed twelve volumes. Neale estimated that Bierce, at the age of sixty-six, had earned no more than one hundred dollars from all of his works in book form combined, most of which had sold no more than a few hundred copies. There were three separate bindings of The Collected Works, the first an expensive autographed edition in a leather motif limited to 250 sets at $120 a set. A critical backlash ensued as the twelve volumes were published between 1909 and 1912. A prickly Neale wrote defensively: “Bierce’s enemies among book reviewers were affronted. Loud were their outcries: ‘Potatoes set in platinum!’ ‘Turnips in Tiffany’s window!’ ‘Pure piffle in plush pants!’ were some of the derisive comments.” But biographer Carey McWilliams noted: “There was absolutely no demand for a ‘collected’ edition of his works; the entire project was pure vanity. Bierce knew that much of the material reprinted was worthless.” Fifteen years after the twelfth volume of The Collected Works was published, Mencken weighed in negatively: “I have a suspicion, indeed, that Bierce did a serious disservice to himself when he put those twelve volumes together. Already an old man at the time, he permitted his nostalgia for his lost youth to get the better of his critical faculty, never very powerful at best, and the result was a depressing assemblage of worn-out and fly-blown stuff, much of it quite unreadable. If he had boiled the collection down to four volumes, or even to six, it might have got him somewhere, but as it is, his good work is lost in a morass of bad and indifferent work. I doubt that anyone save the Bierce fanatics aforesaid has ever plowed through the whole twelve volumes. They are filled with epigrams against frauds long dead and forgotten, and echoes of old and puerile newspaper controversies, and experiments in fiction that belong to a dark and expired age.”  Mencken was on to something, for The Collected Works [republished in 1966 by the Gordian Press] is permeated with undated and unexplained references to people and events, many obscure and remembered no more. Ever defensive, Neale charged that “...ignorant literary critics, through long abusiveness, blind prejudice, and deep hatred of the man, to say nothing of jealousy, probably had made dents in the otherwise immaculate statue. ... However, The Collected Works soon put Bierce where he belonged: in the first rank of world authors.” Neale, of course, had a vested interest. He claimed to have spent more than $40,000 on the project, finding it necessary to borrow $7,500 by securing a chattel mortgage; however, he declared that he paid off the mortgage within six months, and that Bierce, in his final interview, told a reporter that his royalties were sufficient for his needs. Bierce departed from Washington by train on October 2, 1913, ostensibly to join Pancho Villa’s revolutionary army. His final letter to the States [to his secretary and live-in companion Carrie Christiansen] was dated December 26, 1913, and postmarked Chihuahua. Just how and exactly where Bierce died remains one of the great mysteries of the twentieth century. Mencken wrote of Bierce, “Death to him was not something repulsive, but a sort of low comedy—the last act of a squalid and rib-rocking buffoonery. When, grown old and weary, he departed for Mexico, and there—if legend is to be believed—marched into the revolution then going on, and had himself shot, there was certainly nothing in the transaction to surprise his acquaintances. The whole thing was typically Biercian. He died happy, one may be sure, if his executioners made a botch of dispatching him—if there was a flash of the grotesque at the end.” Mencken was ultimately uncharitable to the man who many believe was Henry’s most important influence—although he conceded that Bierce was the first writer of fiction ever to treat war realistically. “It is common to say that he came out of the Civil War with a deep and abiding loathing of slaughter—that he wrote his war stories in disillusion, and as a sort of pacifist. But this is certainly not believed by anyone who knew him, as I did in his last years. What he got out of his services in the field was not a sentimental horror of it, but a cynical delight in it.” The younger author’s blunt perspective of Bierce was not shared by all. In a slim, early appraisal of Bierce, the writer Vincent Starrett says, “Bierce has been called a Martian; a man who loved war. In a way, I think he did; he was a born fighter, and he fought, as he later wrote, with a suave fierceness, deadly, direct, and unhastening. He was also a humane and tender spirit.” Mencken’s ultimate judgment of Bierce was severe. “There was nothing of the milk of human kindness in old Ambrose; he did not get the nickname Bitter Bierce for nothing. What delighted him most in this life was the spectacle of human cowardice and folly. He put man, intellectually, somewhere between the sheep and the horned cattle, and as a hero somewhere below the rats. ...I have encountered no more thorough-going cynic than Bierce was. His disbelief in man went even further than Mark Twain’s; he was quite unable to imagine the heroic in any ordinary sense. Nor, for that matter, the wise. Man to him was the most stupid and ignoble of animals. But at the same time the most amusing.” Those who actually knew Bierce would have been shocked by Mencken’s harsh assessment of a man with whom the younger author was barely acquainted. While Bierce may have had a jaundice view of mankind, he also earned a legion of loyal friends over a lifetime and scores of disciples. Starrett quotes an unnamed friend of Bierce: “His private gentleness, refinement, tenderness, kindness, unselfishness, are my most cherished memories of him. He was deeply—I may say childishly—human... He had no vanity; his insolence toward the mob was detached, for he was an aristocrat to the bottom of him. But he would have given his coat to his bitterest enemy who happened to be cold.” In his final years at the Olympia Apartments, 1368 Euclid Street, NW, in Washington, Bierce served Sunday morning breakfasts for “literary and brain workers," and brewed coffee in a peculiar pot shaped like a melon. Hardly the image of Bierce conceived in Mencken’s imagination.  Bierce’s final home, 1368 Euclid St., NW, Washington, DC Mencken maintained in Prejudices that Bierce spent the last quarter of a century in voluntary immolation on a sort of burning ghat (In India, a series of steps leading down to water, often where cremations occur), worshiped by his small band of zealots, but almost unnoticed by the human race. Mencken also noted there was no adequate life of Bierce, and doubted if any would ever be written. In fact, in 1929 alone four full-scale biographies, memoirs, or portraits of Bierce would be published, as well as important biographies in 1951, 1968, and 1996, not to mention numerous critical studies and at least three significant Internet sites, including The Ambrose Bierce Site. Bierce is also the featured player in Carlos Fuentes’ novel The Old Gringo [filmed with Gregory Peck as Bierce], and as a sleuth in several popular novels by Oakley Hall. A number of his short stories have been filmed. Unlike many writers of his era, the best of Bierce’s work is still being read. Elements of his Collected Works aside, his fiction holds up. In a 2005 book of essays, Kurt Vonnegut wrote, “I consider anybody a twerp who hasn’t read the greatest American short story, which is ‘Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ by Ambrose Bierce. It isn’t remotely political. It is a flawless example of American genius, like ’Sophisticated Lady’ by Duke Ellington or the Franklin stove.” Mencken has himself gone through a reassessment since his death in 1956. Many of his autobiographical manuscripts, his literary correspondence, and his diary were published posthumously, and the diary, with references thought by many to be anti-Semitic, created a firestorm, which is still unsettled. Charles Fecher, editor of the Mencken diary, states unequivocally that Mencken was an anti-Semite: “Mencken rose above many—even most—of the common prejudices and stereotypes of his day, and ought to have been able to rise above that one too. When all is said and done, there probably is no defense. One cannot ask that he be forgiven, or even excused. About all one can do is ask the reader simply to accept the fact and pass on.” William Manchester, whose biography of Mencken was published in 1951, rushed to the defense of his longtime confidant in a letter to The New York Times on February 4, 1990: “Mencken has been silent for 34 years now. His work stands, and it towers. He was a master polemicist; he always gave better than he got, and he really needs no defense. But as one who cherishes accuracy in literary history, I am appalled by the distortions of his considerable role in it. And I am deeply offended by the smearing of my old friend by ignorant liberal bigots.” In a 1925 critical study, Isaac Goldberg wrote, “The Mencken legend has been fashioned out of the fear and wonder of his contemporaries; out of the metaphors and similes that bestrew his pages; out of his thousand and one sarcasms, thrusts, parries, insinuations, lofty flights and low buffooneries. He is too good, too bad, to be true; ergo, make him a legend until the distant day arrives on which he is labeled at last and filed away.”  The aged Mencken  The aged Bierce Ambrose Bierce. H.L. Mencken. Their lives overlapped, spanning parts of two centuries. Both were uniquely gifted men of letters in the highest sense of the word. Both are still read and appreciated, and both remain men of controversy. _______________________________________________

Addendum and Correction

Contrary to the assertion in my article, "Ambrose and Henry, " in the spring 2011 issue of Menckeniana, I have found no evidence to support the following: "Henry... urged [Percival] Pollard to travel to Baltimore for treatment. Mencken knew just the place, a small local hospital that specialized in homeopathy... " and that, "During his final illness, Pollard failed to respond to the homeopathic treatment recommended by Mencken, and a brain surgeon, Dr. Harvey Cushing, was called in. "

Mencken, in a letter to Willard Huntington Wright dated December 20, 1911, writes, in part: "A month or so ago headaches seized him [Pollard] and pretty soon he began to show signs of mental disturbance. On December 5, the bonehead horse-doctors at Milford [Connecticut] having diagnosed grip, his wife brought him to Baltimore for treatment. Unfortunately she landed him, before I knew anything about it, in an E flat homeopathic hospital. There nothing seems to have been done for him. The homeopaths said he was getting on "nicely"--and Mrs. Pollard went back to Milford to lock up the house and get some clothes. While she was away Pollard was suddenly paralyzed and became unconscious. That was last Sunday a week. I was out at dinner and couldn't be found, but an old fellow named Burrows, who knew Pollard, happened to drop into the hospital and found out what was going on. He set up a loud and righteous bellow and demanded a consultation with Harvey Cushing, of the Johns Hopkins, the greatest brain surgeon in America. Cushing diagnosed a brain abscess and decided to operate at once. " With appreciation to Oleg Panczenko of The Mencken Society for citing Mencken's letter, published in The Letters of H. L. Mencken (NY: Knopf, 1961). --Don Swaim _______________________________________________

Sources: Bierce, Ambrose. The Enlarged Devil’s Dictionary. Ernest J. Hopkins, editor. New York, 1967. _______. A Sole Survivor. S.T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, editors. Knoxville, 1998. _______. Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. San Francisco, 1891. _______. Write it Right. Washington, 1909. Dunsmore, Cora T. “Percival Pollard: The Iowa Connection.” Books at Iowa 23. Iowa City, 1975. Fatout, Paul. Ambrose Bierce: The Devil’s Lexicographer. Norman, OK, 1951. Goldberg, Isaac. The Man Mencken. New York, 1925. Hobson, Fred. Mencken: A Life. New York, 1994. Kemler, Edgar. The Irreverent Mr. Mencken. Boston, 1950. McWilliams, Carey. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. New York, 1929. Mencken, H.L. Diary of H.L. Mencken, The. Charles Fecher, editor. New York, 1989. _______. The Impossible H.L. Mencken. Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, editor. New York, 1991. _______. My Life as Author and Editor. New York, 1993. _______. Prejudices: Sixth Series. New York, 1927. _______. Thirty—five Years of Newspaper Work. Baltimore, 1994. Neale, Walter. Life of Ambrose Bierce. New York, 1929. O’Connor, Richard. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. London, 1968. Pollard, Percival. Their Day in Court. New York and Washington, 1909. Stenerson, Douglas C. H.L. Mencken, Iconoclast from Baltimore. Chicago, 1971. Teachout, Terry. The Skeptic. New York, 2002. _______________________________________________

Originally published in the spring 2011 issue of Menckeniana, a scholarly online quarterly published by the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. The magazine is available by subscription. Go to: Menckeniana. Membership in the H.L. Mencken Society includes a subscription. Go to: Mencken Society ________________ Related: “Bierce Duels with the Sage of Baltimore.” Fiction by Don Swaim. Click HERE.

|

|

|

click to buy |