|

Vincent Starrett (1886-1974) was a newspaperman, bibliophile, fiction writer, and an enthusiastic collector of all things Bierce. Perhaps the most dedicated Sherlockian of all time, Starrett considered Bierce a great writer, great master of English, great man, and “possibly the most versatile genius in American letters.” Starrett published an early (1922) bibliography of Stephen Crane, which is interesting because, like Bierce, Crane wrote of the Civil War, although, unlike Bierce, Crane was born well after that un-brotherly holocaust.

Starrett himself would be the first to deny the label “scholar.” “I am no mystic,” he once said. ”I am simply a journalist trying to tell a story, and the stories I tell are about books and authors.” Nor, he said, was he a critic. “...I have never been one; I am a student of literature who writes for other students...”

More than once, the delightfully eccentric Starrett had the opportunity of relocating from his hot, cold, and windy base of Chicago for balmy California — but he refused because he didn’t want to be in the line of fire when the Japanese invaded.

This effort does not attempt to cover all Ambrose Bierce scholarship, which is voluminous, but focuses on the earliest and most significant, and the road leads to Vincent Starrett.

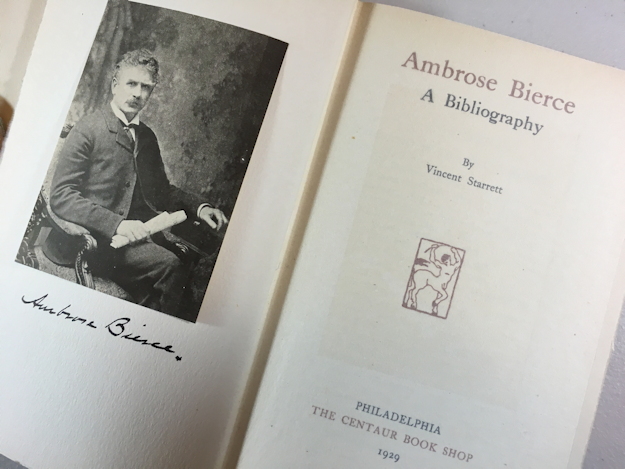

A romanticized Vincent Starrett

photo by Don Loving

One of the prime specimens in Starrett’s personal Bierce hoard was a broadside (a sheet of paper printed only on one side) titled “How Blind Is He,” a holograph stanza written by Bierce for Miss F. Soulé Campbell, published circa 1896 as a photographic facsimile in a printing of perhaps a dozen. Starrett called it “the rarest of Bierce curiosities,” never for sale, and given to him by Bierce’s secretary/companion, Carrie Christiansen (who committed suicide in San Francisco in December 1920 by swallowing Bichloride of Mercury, which has the same effect as lye).

While Starrett’s lifetime overlapped with Bierce’s, the two never met. But not without an effort on Starrett’s part.

from Born in a Bookshop

by Vincent Starrett

One of the first things I did in Washington [after arriving as a war correspondent for The Chicago Daily News], when I had a free evening, was to call upon Ambrose Bierce. That was the intention anyway: but when I established a connection it was not with Bierce that I spoke. Major Bierce, said his secretary [Carrie Christiansen], was not in Washington. It was a disappointment. For years I had been looking forward to a meeting with the author of Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, with whom a few years before I had exchanged letters. He was one of the highest peaks in my whole mountain range of literary idols, and the prospect of meeting him in Washington had helped to make my assignment exciting. Something about my breathless inquiry and my obvious disappointment must have touched the secretary, for she invited me to call.

Starrett did call upon Christiansen only to learn that Bierce had vanished in Mexico the year before.

Nearing his seventy-first birthday and afflicted with asthma, the remarkable old man had suddenly decided to visit Mexico during the winter of 1913, hoping to meet the revolutionary leader Francisco Villa, whom he admired. Several letters had been received by his daughter Helen shortly after his arrival in the southern republic. It appeared that he had joined a division of Villa's army, and mention was made of a prospective advance on Ojinaga. And that was all; the rest was silence.

Bierce’s disappearance was not generally known at the time, and Starrett was the first to break the story.

To me, it was a more important matter than the war in Europe and I lost no time in putting it on the wire. My short dispatch, which appeared on the first page of the Daily News next day, was a clean news beat, but it did not ally the disappointment I felt at missing Ambrose Bierce. Thereafter I saw Miss Christiansen a number of times, and we corresponded almost to the day of her death. I have no reason to believe she knew any more about the writer’s disappearance than she told me at our first meeting, although the publicity my revelation developed gave rise to several romantic legends.

For the rest of my stay in Washington, needless to say, I bothered the departments of War and State almost daily for tidings of Bierce, thus keeping the search for him alive as far as possible; but nothing came of it except new rumors, new falsehoods, and new disappointments.

Starrett’s scoop, flashed world-wide by the Associated Press, set off a manhunt that to this day has not been resolved.

|

EARLIEST BIERCE SCHOLARSHIP

While Vincent Starrett created literary history’s first book dedicated entirely to Bierce, there were earlier short studies, such as an entry on Bierce in a review of California writers by Ella Sterling Cummins, The Story of the Files, published by the World’s Fair Commission, San Francisco, 1893.

Walter Blackburn Harte [1867-1899] published a monograph regarding Bierce in the New England Magazine of Boston, February 22, 1896. I have not located a copy of this, but Bierce’s most stalwart defender, the critic Percival Pollard, says this “fine” assessment was “poorly circulated.” [Harte is cited in three letters written by Bierce, reproduced in A Much Misunderstood Man, edited by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz.]

As for Pollard, he included an overly-effusive thirty-one page chapter praising Bierce in his essay collection Their Day in Court, published by Walter Neale in 1909. In Chapter 7, Pollard describes Bierce as “...the only American, living in America, who was completely a man of letters, in the finest sense of that term, and who had written what his contemporaries, as well as posterity, must admit as masterpieces.”

Pollard continues, “In satire he was a giant; in short-stories a genius. Look but slightly into his Cynic’s Word Book [The Devil’s Dictionary] and you will find the grammarian, and the artist in English.”

But was Pollard an objective critic? He writes, “Admitted, then, that I have been his friend. What of it? If he did work I thought unworthy, was our friendship to prevent my saying so? Because he became my friend, was I to call all his geese swans? The thing is too ridiculous. I would not mention it, did I know the petty misdemeanors of our critical crew, the littleness of their minds, which cannot fancy in others the virtues they themselves lack.”

In 1924, Albert & Charles Boni published a collection of essays by Paul Jordan-Smith, On Strange Altars, one chapter of which is devoted to Bierce. In it, Jordan-Smith cites a few biographical facts, some of which, such as Bierce’s birthdate and the name of his wife, are incorrect. On a critical level, Jordan-Smith says Bierce wrote “...with an air of impish satisfaction, knowing full well how certain romantic persons would suffer over their sanguinary humors or their occult demonism. ...there is one thing common to all his creations...cruelty of the genius who has seen life with undimmed eyes and proclaims the truth.”

| Another early critic was Percy Holmes Boynton, who included a chapter on Bierce in his collection of essays More Contemporary Americans, published by the University of Chicago Press, 1927. While not as effusive as Pollard, Boynton’s view of Bierce is positive, saying, “...on the aesthetic side he added the delicate perceptions of the portrait painter to the caustic judgments of the cartoonist. ... The intellectual Bierce was always on the offensive; always ready to express himself in brilliant brevities. But the Bierce who wrote of the mysteries and the thrills of individual experience was receptive, deliberate, and deliberative, ready to surrender to a mood in a wise passiveness; willing to court in the shadows the shy thought that would not come out into the sunlight.”

|

|

There was also Mencken, of course, whose Prejudices: Sixth Series in 1927 was both a diabolically-clever takedown and celebration of a man who profoundly influenced his own work. Mencken concludes, “He spent his last quarter of a centurty in voluntary immolation on a sort of burning ghat, worshipped by his small band of zealots, but almost unnoticed by the rest of the human race. His life was a long sequence of bitter ironies. I believe that he enjoyed it.”

ENTER VINCENT STARRETT

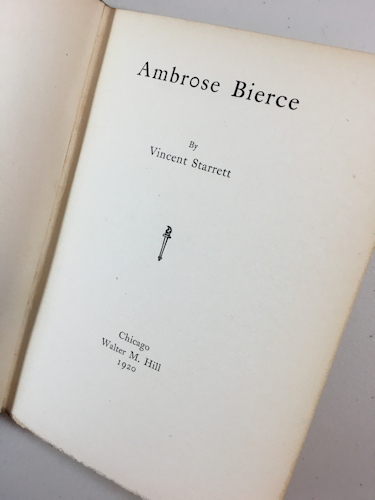

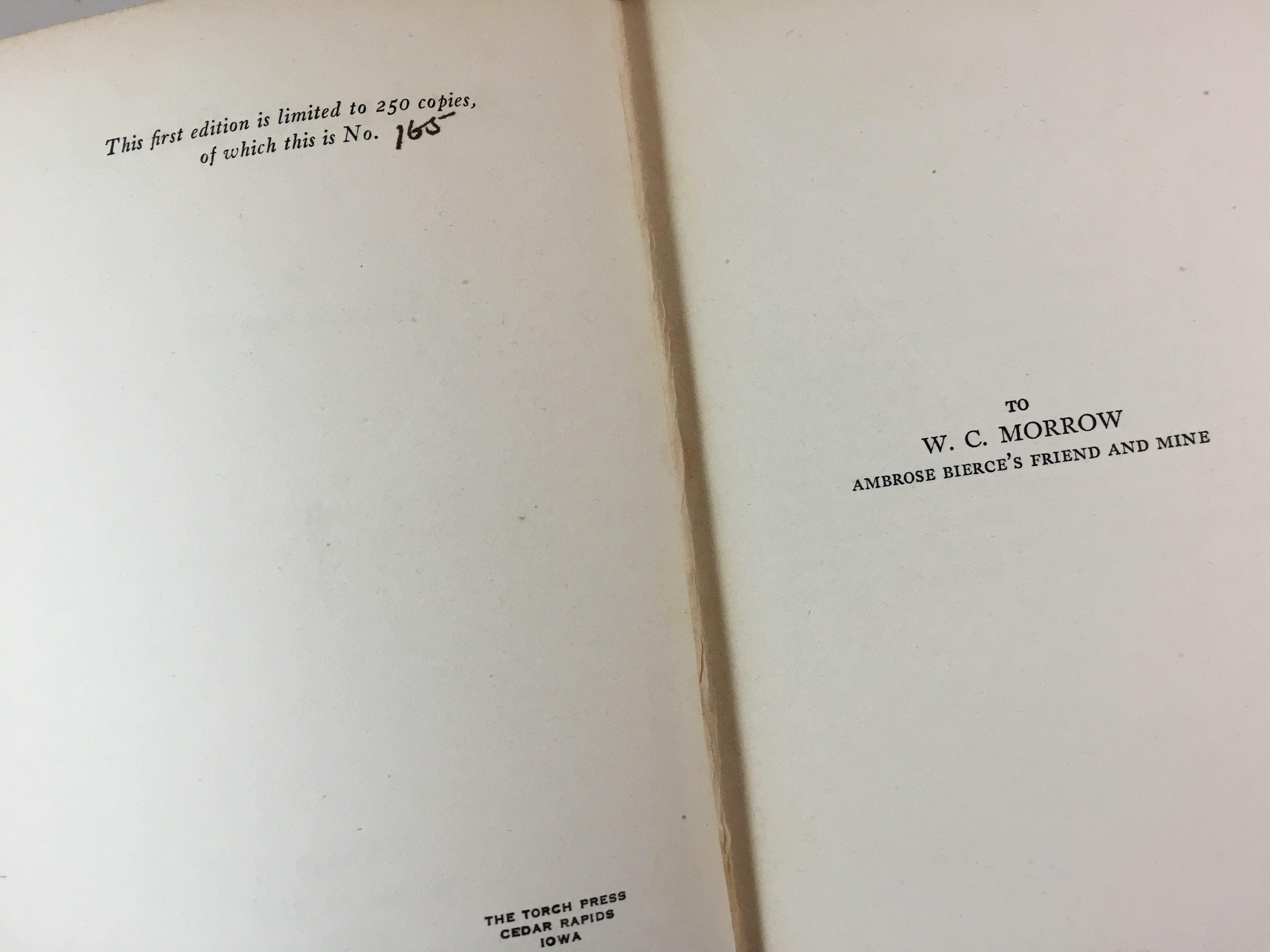

Simply titled Ambrose Bierce, Starrett’s tome was published in 1920 [six years after Bierce’s disappearance and presumed death] by Walter M. Hill, a seller of rare books in Chicago, in an edition of 250 copies. This fifty-page book is divided into three chapters: the first chapter is biographic (although sketchy); the second focuses on Bierce’s Civil War writings; the third on his mysterious disappearance in Mexico (in which Starrett provides no answers). In addition to acknowledging Bierce’s daughter, Helen Bierce Isgrigg, Starrett cites the influence of several others who were personally acquainted with Bierce, including Carrie Christiansen; his publisher Walter Neale (who blatantly capitalized on Bierce’s celebrity); and authors W. C. Morrow and Josephine McCracken.

First Bierce Biography 1920

Starrett was almost apologetic for writing his slim volume, saying, “In the circumstances [following Bierce’s disappearance], it is perhaps presumptuously early to attempt an estimate of the man and his work; but already both fools and angels have rushed in, and the atmosphere is thick with rumor and legend. The present appraisal, at least is not fortuitous, and its stated facts have the merits of sobriety and authority.”

Starrett goes on to say: “It has been said that Bierce’s stories are ‘formula,’ and it is in a measure true; but the formula is that of a master chemist, and it is inimitable. He set the pace for the throng of satirical fabulists who have since written; and his essays...are powerful, of immense range, and of impeccable diction. His influence on the writers of his time, while unacknowledged, is wide. Rarely did he attempt anything sustained; his work is composed of keen, darting fragments. His only novel [The Monk and the Hangman’s Daughter] is a redaction. But who shall complain, when his fragments are so perfect?”

Regarding Bierce’s mysterious disappearance, Starrett concludes, “Setting aside the grief of friends and relatives, there is something terribly beautiful and fitting in the manner of the passing of Ambrose Bierce; a tragically appropriate conclusion to a life of erratic adventure and high endeavor.”

The text of Starrett’s short homage to Bierce was reprinted in Buried Caesars, a collection of Starrett’s literary essays published by Covici-McGee in 1923.

It would not be until 1929 (nine years after Starrett’s book) that the first major biography of Bierce appeared: Ambrose Bierce: A Biography by Carey McWilliams, who, like Starrett, had the advantage of knowing acquaintances of Bierce within his lifetime. Incredibly, three lesser biographies of Bierce were published that same year, some ill informed (by C. Hartley Grattan, Walter Neale, and Adolphe de Castro). McWilliams’s biography remains definitive, with a 1951 biography, The Devil’s Lexicographer, by Paul Fatout, a near second in depth.

The scholar S.T. Joshi told me in 2013, “...there is still no satisfactory biography of Bierce. I hope to write it one day.”

THE LETTERS

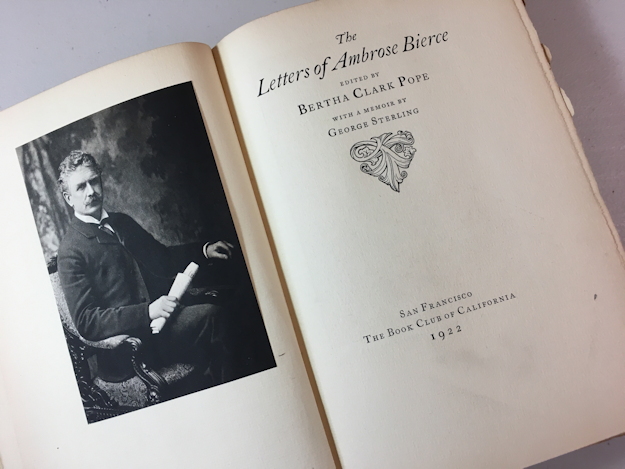

The first two collections of letters penned by Bierce occurred, coincidentally, in 1922. The most important of the two was published by the Book Club of California, edited by Bertha Pope Clark, which included a memoir by George Sterling. The Letters of Ambrose Bierce was issued in December of that year in a printing of 415 copies. While hardly complete, the letters span the period between July 31, 1892, and November 6, 1913. There is also an addendum with undated extracts.

Clark’s introduction is workmanlike, covering biographical details and literary analysis, concluding with, “...Ambrose Bierce is not surpassed by any writer, ancient or modern; it gives him rank among the few masters who afford that highest form of intellectual delight, the immediate recognition of a clear idea perfectly set forth in fitting words — wit’s twin brother, evoking that rare joy, the sudden secret of the mind.”

In his memoir, George Sterling writes of his first meeting with Bierce and his support and encouragement of Sterling’s own work, but does not touch upon their eventual estrangement. Nevertheless, the sycophantic Sterling, who called Bierce “Master,” concludes, “...Bierce is of the immortals.”

The Book Club of California, which was launched in 1912 by a small group of San Francisco literary enthusiasts, published works by Bierce, Sterling, Harte, Clark Ashton Smith, Jeffers, Twain, and many others, and continues to create fine books.

Bertha Clark Pope (1881-1976), editor of the Bierce volume, was employed by the Book of California as a secretary. Born in Connecticut and a graduate of Brown, she is better known as Bertha Damon, the name of her second husband. She achieved some celebrity for a memoir, Grandma Called it Carnal, published in 1938.

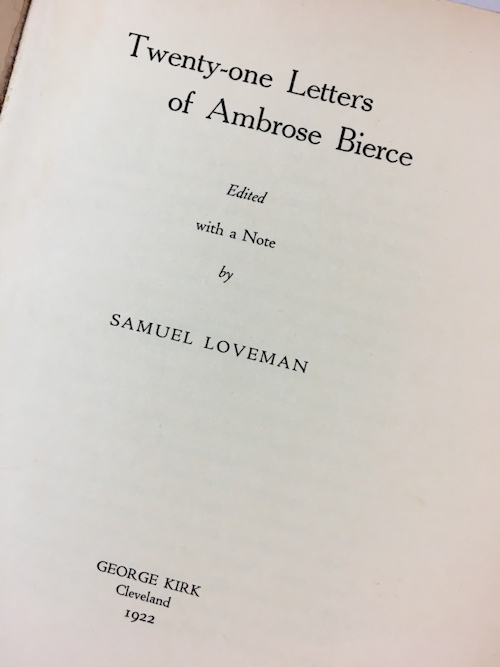

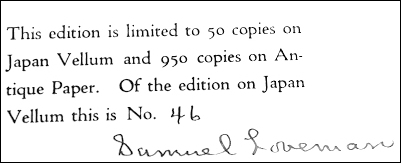

Twenty-one Letters of Ambrose Bierce, edited and with a note by Samuel Loveman, was published by George Kirk, Cleveland, in an edition of 1000 copies, limited to 50 signed copies on Japan Vellum and 950 on Antique paper. These letters cover correspondence from Bierce to Loveman (who calls Vincent Starrett’s early portrait of Bierce, “...brief and notable but wholly ineffective.”) between October 17, 1908, and September 10, 1913.

Loveman (1887-1976), who sought literary authority in his own right, is now remembered through his association with the literary circle that included Bierce, Lovecraft, and Clark Aston Smith. Joshi and Schultz gathered all of Loveman’s known poetry into a volume published by Hippocampus Press in 2004.

FIRST BIERCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

To add to the plethora of material in that bonanza Bierce year of 1929, Vincent Starrett published, at that time, the only Bierce bibliography, a 117-page treasure trove listing all of Bierce’s books, contributions to books and periodicals, plus studies and reviews — through 1929. Published in a hardcover edition of 300 copies by the Centaur Bookshop (founded in Philadelphia 1922 by Harold T. Mason, who also published titles by Cabell, Mencken, Dreiser, and others), another forty-five copies were issued in a paper edition. It remains the unambiguous source of early material.

First Bierce Bibliography, 1929

Starrett asserted that the rarest of Bierce items was a large paper edition of T. H. Reardon’s Petrarch and Other Essays, to which Bierce contributed a memoir. Purportedly, only ten copies were printed, and several were known to have been destroyed.

Another difficult Bierce title to obtain, Starrett said, was the authentic first edition of The Dance of Death by “William Herman,” known as the Author’s Copy (1877), “one of the scarcest items in modern literature.” Thus, the first trade issue of The Dance of Death is actually the second edition, elusive in itself. Condemning the morality of the waltz, The Dance of Death is a hoax widely thought to be the product of Bierce’s fertile imagination, although never confirmed by him.

An amazing act of scholarly achievement was performed by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz in their exhaustive bibliography of Bierce’s work, which was published by Greenwood Press in 1999. It does not, however, in the way of Vincent Starrett, define the elusive and subtle bookish details of interest to collectors of first-edition material.

STARRETT THE BOOKMAN

Vincent Starrett was “born in a bookshop,” metaphorically, in Toronto, where his grandfather was a bookseller, and raised in Chicago. There, he worked as a crime reporter for the Daily News, and later as a war correspondent in revolutionary Mexico in 1914 — an irony not unnoticed as that was the same year Bierce vanished in Mexico.

Starrett was no slouch as a writer himself, celebrated for his detective fiction, which included a recurring Chicago gumshoe named Jimmie Lavender. His most famous book, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, published in 1933, remains the go-to source for enthusiasts of the fabricated sleuth. Starrett was one of the founders of the Chicago chapter of the Baker Street Irregulars, a Sherlockian fan club.

As a poet, Starrett may have been underestimated. In a sonnet dedicated to the fifteenth-century French poet Francois Villon, Starrett writes of the dead Villon’s bones:

They rattle like — Ho, do you catch your breath? —

Like castanets snapped in the hands of Death!

Starrett's best known book, 1933

|

Starrett’s first published book was a monograph on the British novelist Arthur Machen, for whom Starrett later served as literary agent in America. No doubt influenced by Machen’s fantasy and horror tales, not to mention those of Ambrose Bierce, Starrett also wrote supernatural stories, mostly for the pulp magazine Weird Tales. His fantasies were collected in The Quick and the Dead, published by Arkham House in 1965.

Starrett’s infatuation with books was manifested by his Chicago Daily News column, “Books Alive,” and by his many volumes on books, such as Penny Wise and Book Foolish, The Bookman’s Holiday, and Born in a Bookshop, which would unlikely be published today, a culture that rarely thinks of books as sacred objects, particularly in the tactile sense.

|

Book Beat vs. Book Beat

Vincent Starrett was a frequent guest on the first broadcast with the title “Book Beat,” which was launched in 1964 by Robert Cromie, book editor for the Chicago Tribune. The author interview show originated at WTTW, Channel 11, PBS, in Chicago each Monday night, and was syndicated to some sixty PBS TV stations until 1980. The show won Cromie, who died in 1999 at the age of ninety, a Peabody Award.

My own more modest radio feature, “Book Beat,” began in 1982, and was broadcast three times a day on WCBS-AM, New York, and syndicated by the CBS Radio Stations News Service. It ended in 1993. —DS

|

If I had been fully aware of the Starrett-Bierce connection in Mexico, I might have added Starrett to the cast of characters in my novel The Assassination of Ambrose Bierce: A Love Story. Two of Starrett’s colleagues in Mexico at the time, Jack London and Richard Harding Davis, are in the book. Starrett, as a prolific, literarily-oriented Midwesterner, is someone I would have wanted to meet. His papers, including manuscripts and correspondence, are archived at the Lilly Library at Indiana University in Bloomington.

Starrett's signature

REFERENCE

Betzner, Ray. Studies in Scarlett. Vincent Starrett blog.

Bierce, Ambrose. The Letters of Ambrose Bierce, edited by Bertha Pope Clark. SF, 1922

_____________. Twenty-one Letters of Ambrose Bierce, edited by Samuel Loveman. Cleveland, 1922

Boynton, Percy H. More Contemporary Americans, Chicago, 1927

Joshi, S. T. and David E. Schultz. A Much Misunderstood Man, Columbus, 2003

Pollard, Percival. Their Day in Court. Washington, 1907

Ruber, Peter. The Last Bookman. New York, 1968

Starrett, Vincent. Ambrose Bierce. Chicago, 1920

_____________. Ambrose Bierce: A Bibliography. Philadelphia. 1929

_____________. Bookman’s Holiday. New York. 1942

_____________. Born in a Bookshop. Norman, 1965

© 2016 by Don Swaim

Don Swaim is the author of The Assassination of Ambrose Bierce: A Love Story, published in 2016 by Hippocampus Press, New York. HERE.

Top of Page

| |