Stuart Cummings Ripley was born on

March 3, 1892, in the small Ohio town of Cummings, founded

and named by his illustrious ancestors, not the least of

whom was the Reverend John C. Cummings, who was involved

with the Underground Railroad during the Civil War, and

who is mentioned twice in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle

Tom's Cabin. The Reverend Cumming's home has been restored

and is maintained by the Ohio Historical Society. Except

for the local college, the Cummings home is the community's singular

attraction.

Ripley Ancestral Home (before restoration)

Ripley Ancestral Home (before restoration)At the time of Ripley's birth, Cummings was, and is, a farming

community, although Stuart's father, Horace John Ripley, practiced

law and was one of only two attorneys in the county. Stuart's

mother, Susannah Abigail Cummings, was a direct descendent

of the town's founders and a founding trustee of the local

college. One of young Stuart's proudest moments was winning his first-grade spelling bee during which he spelled correctly the word "antidisestablishmentarianism." Stuart attended the college for two years before

withdrawing, against his parents' wishes, to first work for

the local newspaper, and later as a foreign correspondent.

While Ripley's father was an amateur poet who encouraged

his son's literary interests, his mother was an aggressive

outdoorswoman, molding young Stuart into a self-reliant, sometimes

heroic, persona. The influences of each parent played a role

during Stuart's off and on career as a correspondent, most

notably in Mexico, the Middle East and Europe during World

War One, and the Spanish Civil War. Stuart's dispatches for

the leftist New Masses Journal in New York about the war in

Spain were instrumental in prompting Americans to enlist in

the anti-fascist Lincoln Brigade.

Ripley's mother and father, Horace and Susannah

Ripley's mother and father, Horace and SusannahAs a fledgling journalist for a far-left magazine, Ripley

covered General John Pershing's fruitless incursion into Mexico

in search of Pancho Villa. Three years later Ripley's eye-witness

experiences led to his first book, a fictional account of

the Battle of Carrizal, in which thirty-five Americans were

killed or captured by the Mexican Army. Later, Ripley claimed

he'd shot to death two Mexicans in order to escape. The novel,

Catastrophe at Carrizal (1919), went virtually unnoticed.

Edmund Wilson, in his collection of essays, The Triple

Thinkers (1938), while dismissing Catastrophe at Carrizal

as Ripley's fugitive work, also described him as "America's

greatest forgotten author."

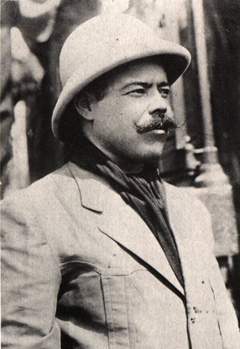

Pancho Villa

Pancho VillaIn 1917, Ripley went to Palestine to report on General Edmund

Allenby's capture of Jerusalem from the Turks, and where Ripley

became acquainted with T.E. Lawrence, the enigmatic British

warrior who often dressed in Arab garb and who was often called Lawrence of Arabia. It was said that Ripley

often rode with Lawrence, and that the two jointly abused

a homosexual Arab male reputed to have been a spy. Ripley's

experiences in the Holy Land led to three novels, now known

as the "Desert Triad."

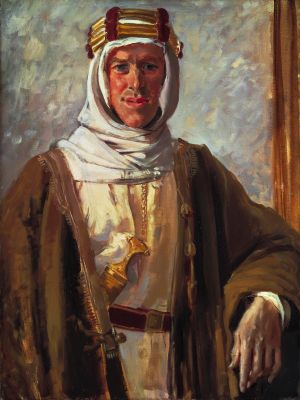

Lawrence of Arabia

Lawrence of Arabiahe following year, Ripley was in Europe

to cover the German siege of Paris. and after the armistice became part of

an

expatriate community that included Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood

Anderson, Djuna Barnes, Kay Boyle, John Dos Passos, F. Scott

Fitzgerald, Ford Madox Ford, H. D. (Hilda Doolittle), Henry

Miller, Ezra Pound, and

Gertrude Stein. It was rumored, although

he would neither confirm or deny it, that Ripley slept with

both H.D. and Dos Passos.

Young Ripley with Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), rear,

Young Ripley with Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), rear,

Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, ca. 1924

In Marseille, he met and romanced

the woman who would become his first wife,

Fleur Beauvais,

nineteen years old, and said to have been an upscale and exclusive prostitute. While their marriage was not to last, it inspired

Ripley's most significant book of poetry,

Fleur (1924). Although Ripley published a number of small, limited editions of his poetry,

Fleur was his most influential and erotic work.

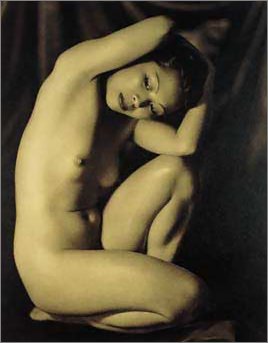

Fleur Beauvais

Fleur BeauvaisWeary of Europe, which he concluded was "decadent," his

marriage over and recovering from STD, Ripley returned to Ohio, only to find

the Midwestern experience stultifying, although it led to

one of his most important works, My Town (1928), which

focused on the hypocrisies of middleclass Americans.

Moving to a basement apartment on Jones Street in New York's

Greenwich Village, Ripley helped to launch a small but influential

monthly, Commonality. At the time, he was thought to have

been involved with the Communist Party, although it was never

established he was actually a member. He also met the woman

who would become his second wife, Sally Beacon, herself an

aspiring writer, poet, and admitted Communist Party member.

Their marriage produced one son, Thaddeus, who in turn provided

the couple with a grandson, Stuart Providence Ripley.

Ripley's brownstone, Greenwich Village, ca 1933

Ripley's brownstone, Greenwich Village, ca 1933The 1930s resulted in Ripley's most prodigious literary output.

Moving with Sally to a rented cottage in Sag Harbor, Long Island, he

published no fewer than four novels, two books of essays,

and a memoir about his expatriate days in Paris. None of the

books created interest, and Ripley's financial situation was

dire, saved only by the small inheritance he received following

the deaths of his parents and the sale of their home in Cummings,

Ohio. Ripley's connection with the photographer Walker Evans produced a notable nude portrait of Sally.

Sally Beacon, second wife, ca 1936

Sally Beacon, second wife, ca 1936

photo by Walker Evans Ripley, on assignment by the Ashtabula, Ohio, Star Beacon, covered the Spanish Civil War in the company of Ernest Hemingway, who introduced him to playwright Lillian Hellman, with whom it is believed Ripley had an affair. It was during this period that Ripley had a falling out with Hemingway, although the circumstances aren't completely clear. Ripley's association with the Lincoln Brigade captured the attention of right-wing communist witch hunters in the 1950s.

In 1939, Ripley's wife Sally committed suicide by drowning

in Long Island Sound. The tragedy resulted in a long period

of depression during which Ripley was unable to write. He

emerged from his depressed state only after the start of World

War Two, when he resumed his career as a foreign correspondent,

filing dispatches from both Europe and the Pacific for the

Hartford Courant. While not mentioned in any of his

reports, it's said that Ripley personally killed two Japanese

soldiers at Leyte. Ripley's best reportage was collected in

In Time of War (1946). After Hiroshima, Ripley went to Japan, where rumors circulated that he had a "relationship" with the woman known as Tokyo Rose, who was being held prisoner on war crimes charges.

Tokyo Rose

Tokyo RoseLeaving Japan, Ripley returned to New York City to act as an English instructor at City College of New York. His

three stage plays, all produced off-Broadway by the East Side

Experimental Theatre Company, were well-received. He met a

young actress, Jill Castenberry, with whom he maintained an

intimate relationship for the rest of his life, although they

never married.

In 1952, Ripley was summoned by the House Un-American Activities

Committee to testify about his alleged links to the Communist

Party dating to the early 1930s. Ripley, denying he was a

party member, nevertheless named some of his associates of

the period, which produced enmity on the part of many of his

friends who accused him of betrayal. It also led to his dismissal

from CCNY. His screenplay of his 1938 novel Angel in the Clouds

was abruptly pulled without explanation. Dramatically, he

found himself more and more isolated.

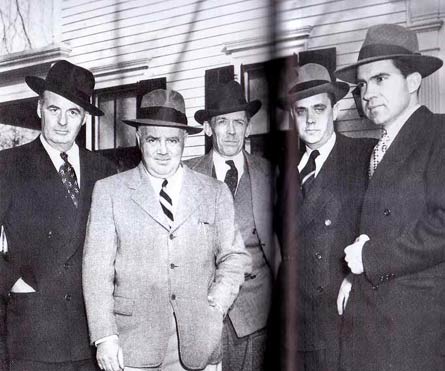

Ripley's disquinished inquisitors on the HUAC

Ripley's disquinished inquisitors on the HUACRipley and Castenberry moved to a small grape-growing farm

in Uhlerstown, Pennsylvania, a tiny community on the Delaware

River. Drinking and smoking heavily, and deeply depressed,

Ripley's literary output decreased, although it still included

two novels, unpublished in his lifetime, and an unfinished

biography of his mother. Unable to write, he turned to cooking

and became an accomplished amateur chef and vintner. His only

published book during this period, Recipes by Ripley,

was printed by the nearby Bethany Baptist-Methodist Church

as part of a fund-raising drive.

Ripley, Bucks County, 1964

Ripley, Bucks County, 1964A chain-smoker and heavy drinker, Ripley died in a Philadelphia hospital following a heart attack on February 2, 1964. He was seventy-two. He left no known will. Just prior to her death in 1988, Jill Castenberry donated Ripley's papers and manuscripts to Cummings College.